Overview

1. Summative and formative feedback

2. The dialogical character of feedback

3. Written and oral feedback

4. Transparency and clarity

5. Feedback as support for effective learning

6. Student responsibility

7. Tips on designing feedback for writing assignments

7.1. Plan your feedback

7.2. Practical example: Model feedback sequence

7.3. Use feedback to facilitate dialogue and motivate and encourage students

7.4. Commenting on writing assignments (from the first draft to the final

version)

Thoughtful and appropriate feedback on writing assignments is a powerful instrument for teachers to support student learning.[1] However, as most teachers know from experience, providing feedback is a lot of work. The challenge lies in designing specific and efficient feedback that helps students achieve the best possible, sustained learning success.

This article, based on the introductory text Teacher Feedback, deals with feedback varieties for writing assignments, conditions for successful feedback practices (even in large classes), and the challenges for teachers and students. It closes by offering concrete practical advice on implementing feedback in the classroom.

1. Summatives und formatives Feedback

Courses with continuous assessment provide a frame for teaching concepts that can include both formative feedback (feedback that accompanies the writing process) and summative feedback (feedback on the final draft of a writing assignment). Teachers can decide at which pivotal points during the writing process they prefer to provide feedback (such as the research question, thesis, outline, exposé or proposal, etc.) to support students in their work. Thus, learners get the opportunity to implement feedback while they are still working on their projects. Teachers have the advantage of distributing their work over a longer period of time and therefore of avoiding getting overwhelmed toward the end of the semester.

2. The dialogical character of feedback

Regarding a text as a place of intellectual encounters between authors and readers[2], reveals the significance of the dialogical character, which research has identified as a central aspect of effective feedback.[3] Additionally, the significance of dialogue is not surprising, considering that feedback is an integral component of academic practice, and scholarship itself is widely considered the result of discursive activities. Thus, students should be given the opportunity to learn, comprehend, process and negotiate feedback, as well as react to it. This helps teachers assess if learning is taking place as intended.

However, unidirectional feedback that only consists of information delivered from teacher to student often leads to frustration on both sides, frequently caused by misunderstandings or a lack of understanding.[4] For instance, students may be unsatisfied with the feedback they receive because they do not understand it or it does not address aspects for which they need help most urgently. Teachers, on the other hand, report that only few students collect feedback, or that some students do not pay attention to it or act on it.[5]

It is important to include students as active contributors to the feedback process in order to avoid these problems, as well as to to make feedback dialogical in character and therefore more effective. This requires commitment from students, which teachers can support with appropriate teaching instruments (see Teacher Feedback).

The conditions in which teaching takes place have an impact on what type of feedback can be realized. For example, in classes with large numbers of students we recommend selective feedback (especially in the early writing stages), incorporating collective feedback either in the lecture hall or on Moodle, and using suitable forms of peer-review.

3. Written and oral feedback

Written feedback provides a safe space in which communication between teachers and students remains confidential. It ensures that the person receiving the feedback truly feels like he or she is the intended audience. Written feedback can be carefully worded and it is a permanent document that students can access repeatedly. This is especially useful when students learn complex content and they need time to reflect, or if students are expected to act on the feedback in their subsequent work.[6]

Oral feedback has proven reliable in the following situations: If a text contains numerous problems, then individual conversations with students can cover more ground and save time. If teachers find similar problems in the texts of many students, then a group conversation may be appropriate or teachers can give feedback in the classroom. It is also possible to record collective feedback and make it available as a podcast on Moodle.[7]

4. Transparency and clarity

In order for feedback to be effective, students must understand it. Thus, communicate your expectations in advance, e.g. with clearly defined requirements and using evaluation criteria. Discussing the criteria with your students can clarify potential uncertainties and misconceptions in advance, as they engage with the criteria, and strengthen their understanding of what is expected from them. Feedback and criteria that clearly relate to the assignment create additional coherence. You may also invite advanced students to contribute criteria for feedback and assessment in order to learn and practise the standards in your discipline.

5. Feedback as support for effective learning

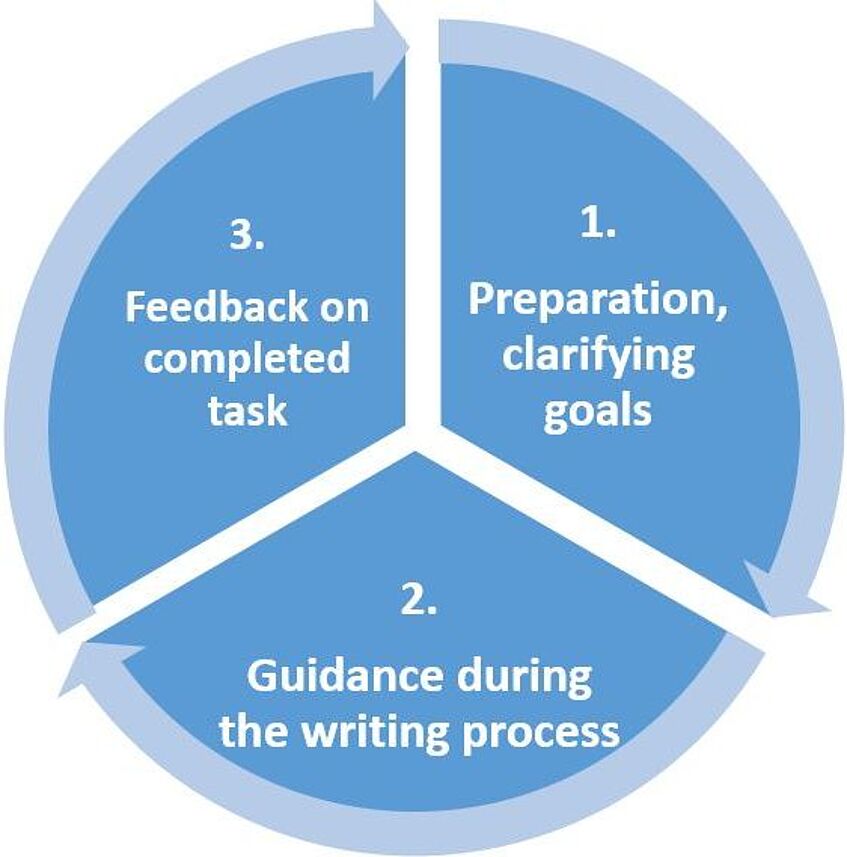

Feedback is most effective when used step-by-step, as part of an ongoing process and in repeated feedback loops.[8] You can implement repeated feedback within one class if your class size allows it, or consider it for larger units within your curriculum (e.g. courses that build on one another, modules). The following example illustrates a sustainable feedback process as a dialogic feedback cycle that you can fit into your teaching/learning environment.[9]

This cycle consists of three sequences aimed at sustainably supporting student learning when applied repeatedly:

- Preare and clarify the objectives ("feed-up"): Explain and discuss the writing assignment, as well as the assessment criteria in relation to the intended learning outcomes. Some teachers use model examples.

- Guidance during the writing process ("feed-back"): Students receive feedback on hypotheses, outlines, or rough drafts and chapters. They revise their work, taking into account the feedback they received. Peer feedback can also be useful at this stage.

- Improvement-orientated feedback on the final draft ("feed-forward"): Students receive written or oral feedback, which clearly refers to the criteria you discussed earlier. Students apply what they learned from the feedback cycle to future writing assignments (also in future courses). Teachers use their experiences to adapt future assignments.

6. Student responsibility

Feedback is particularly effective in supporting learning when students actively participate in the process. Feedback should be designed in a way that students understand it, and perceive it as both urgent and relevant for taking the next steps, thus encouraging students to respond to it[10]

One possibility for students to assume responsibility for the feedback and adapt it to their own individual learning needs is to identify specific aspects that they would like to receive feedback on, when they hand in papers (or assignments). An additional way to help students become independent and self-reliant dialogue partners is to assign a reflection paper on the feedback they received. In this paper, students discuss what parts of the feedback they find helpful and how they plan to integrate it in their future learning activities.

7. Tips on designing feedback for writing assignments

7.1. Plan your feedback

- We recommend integrating feedback cycles in the early stages of course planning and to consider when and what kind of feedback you will provide and on what elements of student work. In doing so, you are able to tailor feedback activities to the students’ learning progress (where in the curriculum the course is placed and what students should be able to do at this point), as well as create a plan for the duration of the semester. Giving feedback at different times during the semester enables you to plan the learning progress of your students in a structured way, as well as plan your work load appropriately.

- Coordinating feedback with writing assignments has proven especially effective. Ideally, you formulate the criteria for feedback and assessment as you plan the assignment and refer back to them in your feedback. Focusing on a few selected criteria allows you to realise your interventions specifically and sparingly, while simultaneously providing students with reference points they can use to orientate their writing.

- What issues feedback at different stages should address and focus on also depends on whether the written assignment is still in its early stages or close to a final draft. We recommend you first direct your attention to so-called "higher order concerns" (content, ideas, argument, thesis) before turning to "lower order concerns" (grammar, spelling and punctuation, language).[11] It is important for students to receive feedback early (and short), for example on the research question, whereas language and grammar issues may be addressed close to the final stages of the writing process.

7.2. Practical example: Model feedback sequence

This model shows how you can sequence feedback on consecutive phases of a writing assignment during the semester: First, the paper's subject and research question are discussed and clarified (either during office hours or a class session). Then, the outline or the proposal/exposé (including methodology, procedure, etc.) receive feedback. At this point the paper's basic direction should be clear and students can proceed to formulating the prose. You may include a peer review session of the first full draft, before the students submit a revised and final version for assessment. This allows students to practise planning, feedback, and revision, which are integral to academic work, and to acquaint themselves with different priorities in the writing process, i.e. content has priority, language is important but secondary. The common misunderstanding of focusing on form over content can be better avoided this way.

7.3. Use feedback to facilitate dialogue and motivate and encourage students

The following kinds of feedback help students to accept and implement your feedback:[12]

- Selective feedback: Focus your feedback on a few elements of a text, which students can act on easily and therefore allow them to continue their work.

- Specific feedback: Point to the exact place in the paper that your feedback addresses.

- Timely feedback: If you would like students to implement feedback in their subsequent drafts, give them enough time to do so.

- Contextualised feedback: Relate feedback to intended learning outcomes and assessment criteria.

- Balanced feedback: Don't focus exclusively on parts of a paper needing improvement, but make sure to also point out the successful parts.

- Process-orientated feedback: Suggest what your students can do to perform better in future writing tasks.

7.4. Commenting on writing assignments (from the first draft to the final version)

- "Less is more": Use the intended learning progress as a guide when commenting on student writing.[13] If a paper contains a large number of problems, choose a small selection of issues that require the most feedback. Ideally, these are closely linked to subsequent learning steps. This allows you to save time and give effective feedback in a way that minimizes students feeling overwhelmed by too many comments and corrections, and allows them to continue working, while focusing on the suggestions you prioritized.[14]

- Keep your role as a teacher in mind when commenting and grading.[15] Commenting on early phases of the writing process, teachers often find themselves in the roles of learning advisers and coaches. Later they act as evaluators in assessing final versions. Each role requires a different perspective when reading student work. Advisers are typically improvement-orientated and offer support, whereas grading tends to shift the focus to the deficits of a paper. In order to create and maintain a constructive and communicative feedback culture, we recommend you approach student texts from the perspective of an interested reader first, and determine the grade as a last step.[16]

- Wording feedback

- Proper wording can create a friendly and constructive environment for feedback dialogue: Respectful, constructive feedback that is improvement-oriented and points to concrete working steps motivates students and encourages their perceived self-efficacy..[17]

- Especially in the case of formative feedback, concrete questions (instead of conclusive statements) or descriptions of the subjective reading experience have proven more effective than evaluations, as the former allow students to derive further working steps.

- Written feedback can take on the form of summarising comments, marginal notes, or comments/corrections within the text and can be done either by hand or by electronic means. Many teachers use a combination of both. We recommend including a summarising final comment because it directs students' attention to the paper as a whole, as well as to its substance. If you only include marginal notes or corrections within a paper, students who are less experienced writers tend to get caught up in details and lose sight of the big picture.

- If a paper contains many grammatical and spelling errors, we recommend you only comment on one example paragraph in detail. This will allow you to communicate the fundamental issues while encouraging the student to take the responsibility for correcting the rest of the paper. Thus, you avoid taking on the (labour intensive) editing role.

References

[1] Hattie, John, and Helen Timperley. "The Power of Feedback". Review of Educational Research 77, no. 1 (March 1, 2007): 81–112.

[2] See also Kruse, Otto. Lesen und Schreiben. Konstanz: UVK, 2010, 13.

[3] Nicol, David. "From Monologue to Dialogue: Improving Written Feedback Processes in Mass Higher Education". Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 35, no. 5 (August 2010): 501–517.

[4] vgl. Hattie und Timperley, „The Power of Feedback“ [1].

[5] Nicol, „From Monologue to Dialogue“[3].

[6] Jolly, Brian, and David Boud. "Written Feedback: What is it good for and how can we do it well?" In Feedback in Higher and Professional Education: Understanding it and doing it well, eds. David Boud and Elizabeth Molloy, 104–124. London: Routledge, 2013.

[7] Jolly and Boud, "Written Feedback" [6]; on podcasts see Sommers, Nancy. Responding to Student Writers. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2013.

[8] Vardi, Iris. "Effectively feeding forward from one written assessment task to the next". Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38, no. 5 (1. August 2013): 599–610. doi:10.1080/02602938.2012.670197.

[9] Beaumont, Chris, Michelle O’Doherty, and Lee Shannon. "Reconceptualising Assessment Feedback: A Key to Improving Student Learning?" Studies in Higher Education 36, no. 6 (September 2011), 671–687. doi.org/10.1080/03075071003731135.

[10] Kluger, Avraham N., and Angelo Denisi. "The Effects of Feedback Interventions on Performance: A Historical Review, a Meta-Analysis, and a Preliminary Feedback Intervention Theory“. Psychological Bulletin 119, no. 2 (1996): 254–284.

[11] Ulmi, Marianne, Gisela Bürki, Annette Verhein-Jarren, and Madleine Marti. Textdiagnose und Schreibberatung: Fach- und Qualifizierungsarbeiten begleiten. Stuttgart: UTB, 2014, 49f.

http://www.utb-studi-e-book.de/9783838585444 [last accessed on 09.11.2022]

[12] Adapted from Nicol, "From Monologue to Dialogue", 512-513, [3].

[13] Sommers, Nancy. Responding to Student Writers. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2013, 27.

[14] See also Kruse, Lesen und Schreiben, 164f [2].

[15] Gottschalk, Katherine K., and Keith Hjortshoj. The elements of teaching writing: a resource for instructors in all disciplines. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2004, 54f.

[16] Langelahn, Elke. Studierenden Text-Feedback geben – effizient und konstruktiv. Bielefeld: Universität Bielefeld, 2016, 7f. https://www.uni-bielefeld.de/einrichtungen/zll/publikationen/Handreichung_Text-Feedback.pdf [last accessed on 09.11.2022]

[17] Jolly and Boud, "Written Feedback" [6].

Recommended citation

Center for Teaching and Learning: Teacher Feedback on Writing Assignments. Infopool better teaching. University of Vienna, March 2019. [https://infopool.univie.ac.at/en/start-page/teaching-advising/feedback/teacher-feedback-on-writing-assignments/]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Austria License (CC BY-SA 3.0 AT)

For more information please see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/at/